Corcovado

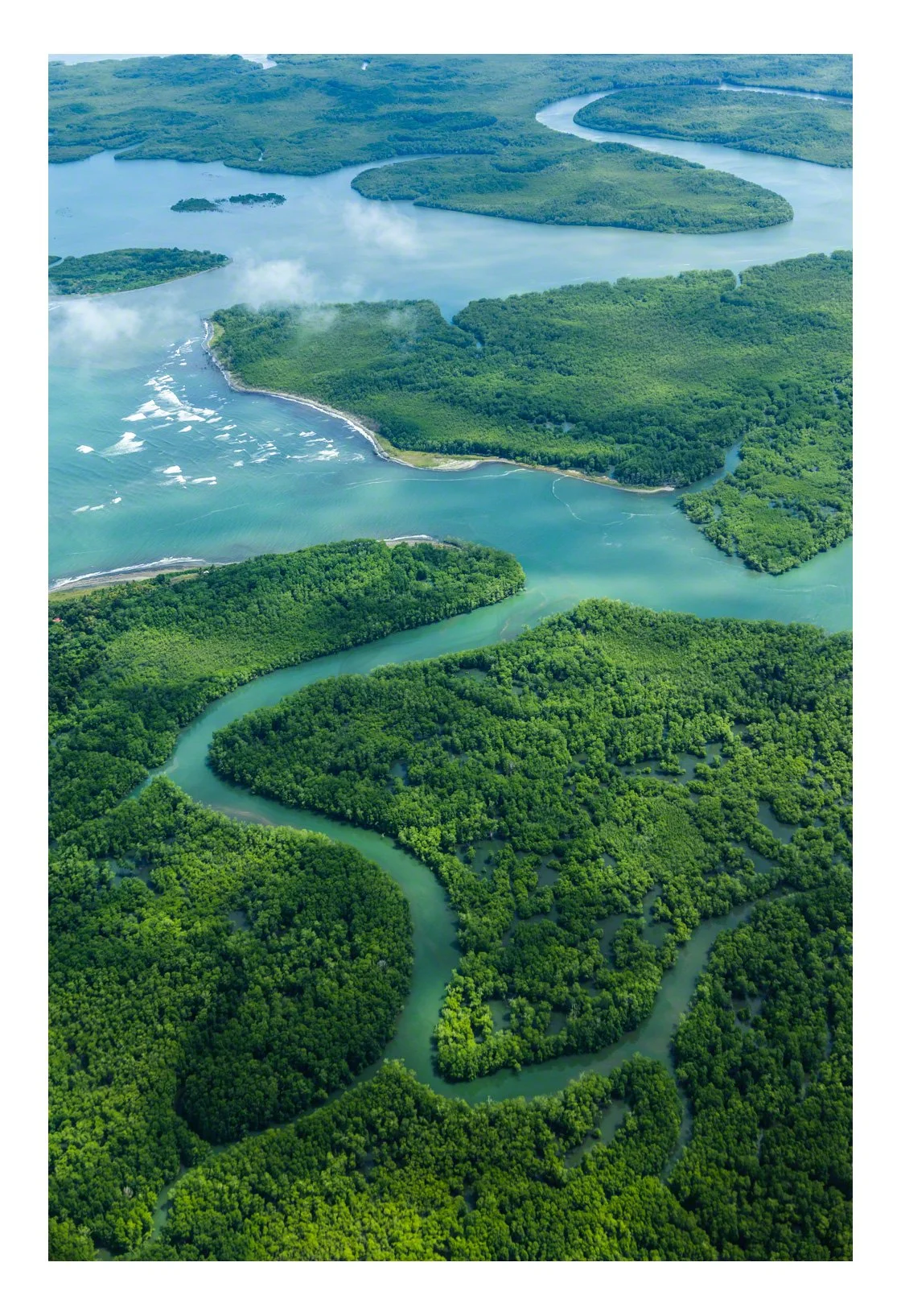

On the west coast of southern Costa Rica lies the Osa Peninsula which is where Costa Rica’s largest national park, Corcovado, can be found.

This peninsula is home to at least half of all species found in Costa Rica, and though it accounts for less than 0.0001% of the earth’s land surface, those species make up 2.5% of all its life-forms¹.

National Geographic considers the Osa Peninsula to be "the most biologically intense place on earth in terms of biodiversity”. Pretty insane.

Not all of the peninsula is part of Corcovado National Park, but even so, more than 80% is protected by this and other national parks². Corcovado itself makes up about one third, weighing in at 424km².

Life in Corcovado seems to emanate from everywhere, be it birds overhead, monkeys in the trees, ants creating mini highways going to and fro, or even crabs popping up out of the sand along the beach.

This here is a little hermit crab. There are, in fact, over 800 species of hermit crab, many of which need to find mobile shelters in the form of abandoned shells. Seeing as these shells are not their own, they don’t grow alongside the crabs which eventually leads to the hermits looking for a new, larger one.

The problem with this, though, is that they never know what they’re going to find. But even finding a shell that is too large can lead to finding the right one. One by one, other crabs of differing sizes will all come and line up, sizing each other up and ordering themselves accordingly from largest to smallest. Then, when one of the crabs decides that they’re ready to move homes and claims the large shell, the second in line will jump out of their shell and dash into this newly abandoned shell, and then the third, and the fourth and so on.

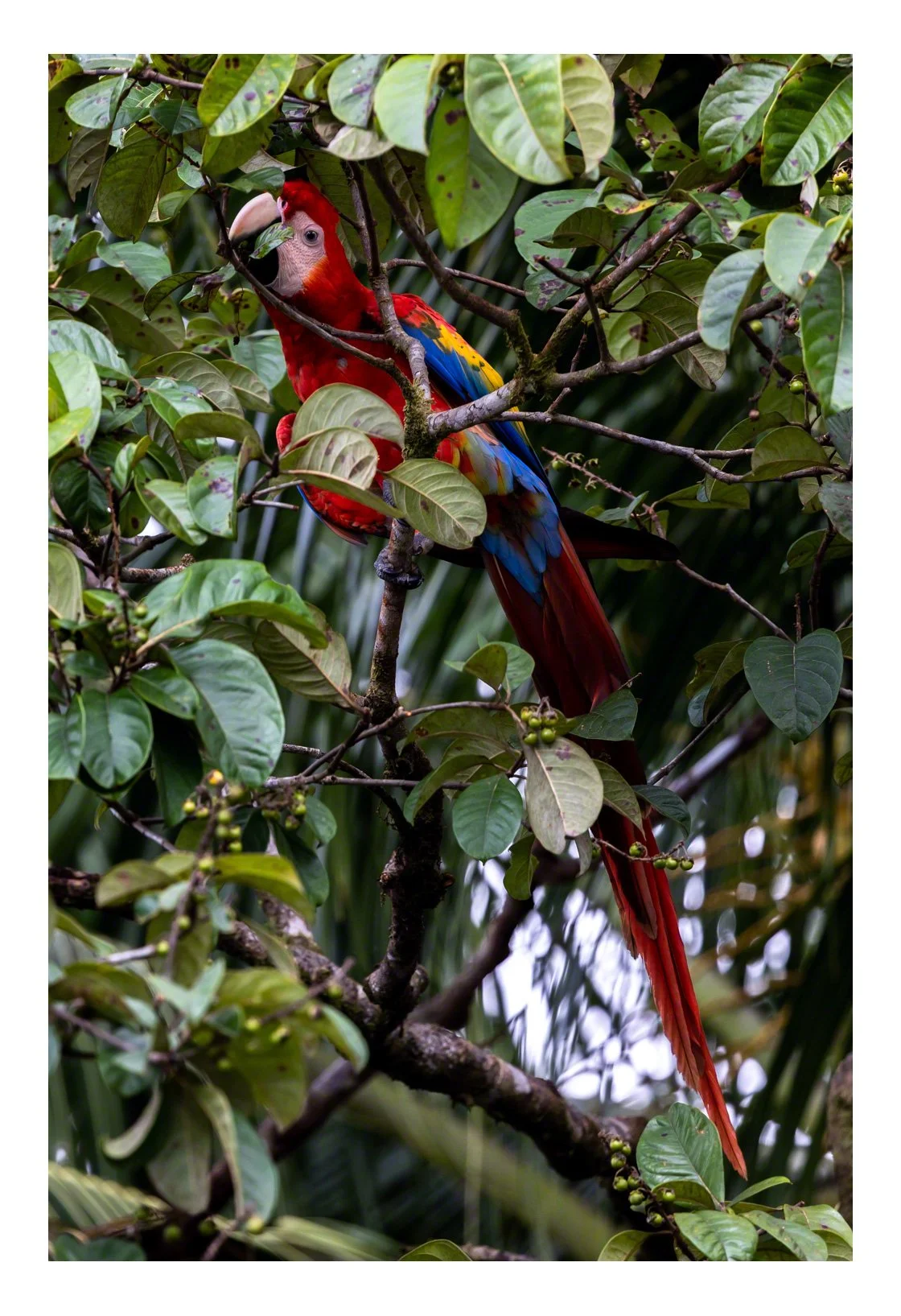

Costa Rica is also one of the places to see the scarlet macaw in the wild, which ranges from up in Mexico all the way down to Brazil and Bolivia, as well as some Caribbean and Pacific islands.

Corcovado is also the only part of the country where you can see all four of its monkey species. On this trip, we managed to find three of the four.

The Howler Monkey

The Spider Monkey

…and the Capuchin Monkey.

Often called ‘Marcel’.

Or cappuccino.

Or '“Oh look! A monkey!”

“Oh look! A monkey drinking from a coconut.”

Also climbing up a tree was an Anteater, no doubt on the lookout for its next meal. Anteaters also eat termites, but the suggestion of naming it a Termiteeater was promptly rejected for being a bit too much.

One of the amusing things about naming animals is that sometimes they can be very literal, as is the case here.

When it comes to naming families and groups of animals, scientists turn to Latin to make things sound a little more… official. But that doesn’t mean they get any more creative...

The anteater, for example, belongs to the suborder Vermilingua which, when broken down, means worm (vermi) and tongue (lingua). Worm tongue… Huh.

It gets better, though, as it is also of the order Pilosa, along with sloths, which means hairy. So the anteater and sloth are distant hairy cousins, along with Cousin Itt.

This little fella is a Coati, and while it may resemble the Termiteeater just above in certain ways, it’s actually a cousin of the Racoon. This is slightly more obvious with some of the other Coatis which, like Racoons, also have white rings on their tails.

This here, though, is the only Coati that lives in Central America – the White-nosed coati. In fact, it’s the only Coati that ranges across South, Central and North America³, ranging all the way from the coasts of Colombia, up as far as Arizona and New Mexico in the United States. The three other Coati species can only be found in South America.

They even communicate with each other by chirping, snorting and grunting, depending on what they’re doing and how they’re feeling. For example, they’ll chirp when they’re enjoying a good grooming from another Coati, or perhaps when they’re irritated, and they’ll snort while digging for food.

Along with grunts and things, they communicate with their bodies, like showing submission by hiding their noses. They also sleep with their noses tucked into their bellies⁴.

In German and Dutch, they’re quite literally called ‘Nose-bears’ – Nasenbär and neusbeer respectively. Although, they’re now believed to be more closely related to things like badgers, otters and ferrets than they are to bears⁵, so perhaps they’ll need a name change, much like the Termiteeater.

And then there’s the tapir. This is a Baird’s Tapir, one of only four living species of tapir. In 2013, a group of researchers claimed to have found a fifth species⁶ – the kabomani tapir – but others weren't so convinced that it really counted and told them to go away. (Except, of course, they probably didn’t.)

They’re typically rather shy. That being said, if you come across a female with an infant in tow, they can become defensive. They have terribly strong jaws, so if they get a hold of you then the results aren’t going to be pretty. When they do get scared, though, they normally opt instead to run in the opposite direction.

References

¹ National Geographic, A loss of tourism threatens Costa Rica’s lush paradise – Published January 12, 2021

² Costarica.com, Osa Peninsula

³ Wikipedia, White-nose Coati range

⁴ National Geographic Kids, Coati

⁵ Flynn, John; Finarelli, John; Zehr, Sarah; Hsu, Johnny; Nedbal, Michael (2005). "Molecular Phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): Assessing the Impact of Increased Sampling on Resolving Enigmatic Relationships". Systematic Biology. 54 (2): 317–337. doi:10.1080/10635150590923326. ISSN 1063-5157. PMID 16012099

⁶ Wikipedia, Tapir Species